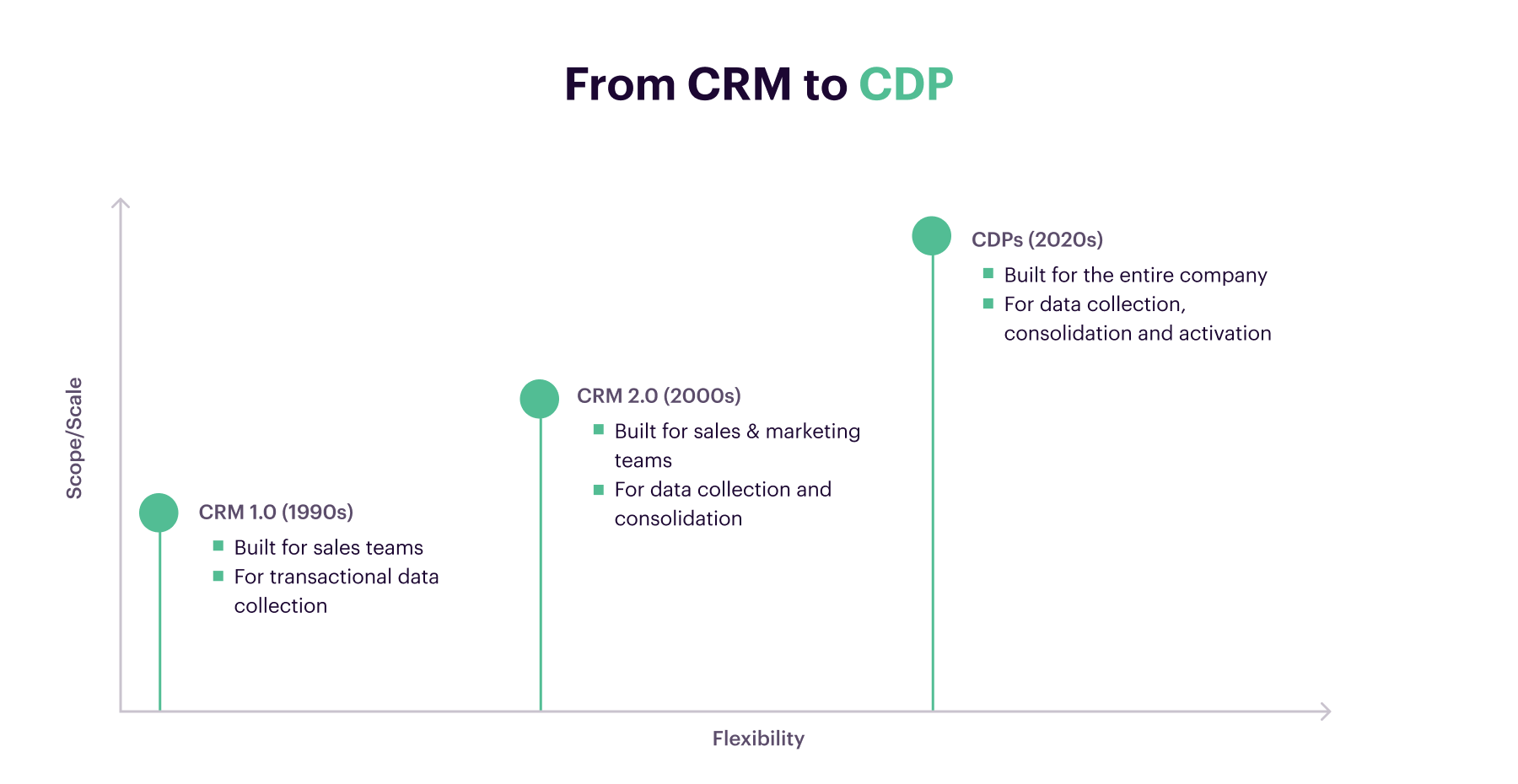

A short history of CRM and the long evolution of CDP

We're about to enter the era of the customer data platform. How did we get here and where are we headed?

We're about to enter the era of the customer data platform. How did we get here and where are we headed?

The Rolodex on the mahogany bureau, the index cards in the cookie tin, the little black book in your back pocket – it’s always been about who you know.

Except, in business as in life, that’s only half the challenge. It’s about who you know and how you nurture that relationship.

Fail to nurture your relationships – if you forget a thank you note, a birthday card, an IOU, or a pink “while you were out” – you risk losing both friends and influence.

Dunbar’s number puts the limit to any one individual’s capacity for maintaining stable relationships at about 150. But companies have limits too.

As the Empire Builders Group’s Amy Larrimore told the New York Times back in 2013, even the smallest database – 200 clients, say, with 500 prospects and 1k leads – is a lot to deal with without a system in place. This is what customer relationship management was supposed to help us fix.

Except, of course, nothing is that simple.

Fast forward to 2020, and CRM tools are only capturing a small fraction of the customer data generated today. From mobile to web, online to offline, in-store to backend systems, payment services to help desks, the singular concept of a customer relationship has never been more fragmented.

A tool that promised to be a single pane of glass is now on the verge of becoming a broken mirror.

How did we get here?

On October 19-22, we'll be hosting CDP Week, the premier industry conference for customer data leaders. We'd love it if you could join us.

The first CRM, according to entrepreneur and an early pioneer in the field, Jon Ferrara, started with humble origins – a list of names and numbers on a VisiCalc spreadsheet on an Apple II sometime around 1979.

It was quickly understood that contact info isn’t all that useful if all you can do is look at it. So developers started writing macros for VisiCalc.

ACT! (a piece of software which, pleasingly, went through six name changes and is now on version #21 of its seventh name) was an early contender.

It was best described as a digital rolodex, featuring a basic method for storing customer contact information.

Act!, or Automated Contact Tracking, launched in 1987, filling the void for customer relationship management.

Meanwhile, a Philadelphia-born car salesman and IBM alumnus, who’d recently hit rock-bottom and filed for bankruptcy (his attempt at creating the internet before the internet failed spectacularly), decided to narrow his visionary focus and write what would be the first actual CRM.

Michael McCafferty called it TeleMagic, releasing an initial DOS version in 1985, and Apple and Unix versions two years later. He said it was an Electronic Rolodex, “but with greatly increased functionality.”

By integrating with word processors and accounting systems, Telemagic didn’t just help you store contact information. It could help you prioritize who you should follow up with.

TeleMagic, one of the earliest known purpose built CRMs.

Ferrara was in sales management at Banyan Vines when he realized that the future wasn’t just about storing contacts. It was about having that information networked to other systems, and then acting on that information.

In 1989, he and a friend, Elan Susser, set up shop in a Woodland Hills apartment in LA, with $5,000 and a dream. It was there they invented GoldMine.

Launched in May 1990, Goldmine fired the first shot in the CRM revolution.

It was the first piece of software to integrate the basic strands of business as we now know it: email contact, calendar, sales, and marketing automation. Crucially, it was not just for the people doing the selling, but for everybody in the company.

We were trying to teach people how to nurture and build relationships as a team when they were still used to being the lone gun. Jon Ferrara

But no sooner had GoldMine netted Ferrara the PC Magazine’s Editor’s Choice honor four times in five years, Microsoft launched Outlook, Siebel hit the market running, and Gartner and IBM entered the fray.

Bigger tectonic shifts were to come.

In the same year, Ferrara sold up – 1999 – Marc Benioff singlehandedly upended the software industry with Salesforce and his pioneering software subscription model. Whereas the early pioneers had been selling CRM software as an on-premise solution, Salesforce predicted the future belonged in the cloud. The CRM 1.0 industry ended the 20th century with the beginnings of a mass migration online.

Marc Benioff in front of the Siebel User Group conference in downtown San Francisco.

By bringing things into the cloud, Salesforce disrupted CRM forever. As long-time commentator Scott Brinker puts it; “You didn't have to deal with all the problems people had with maintaining and updating on-premise software.”

But as CRM moved to the cloud, companies’ focus also shifted – from customer relationships, to collecting the data about the customer. It was a subtle but nonetheless crucial difference.

As Rawn Shah noted:

Rather than helping a specific customer with their needs, which eventually got bucketed under customer service rather than across the company, it became ways to generalize, anonymize, and aggregate individual clients into profiles of behaviors and needs.

“Customer relationships” were fragmented between specialist bits of the business (the sales rep, the call center agent, customer support, etc.) and the resulting data, siloed.

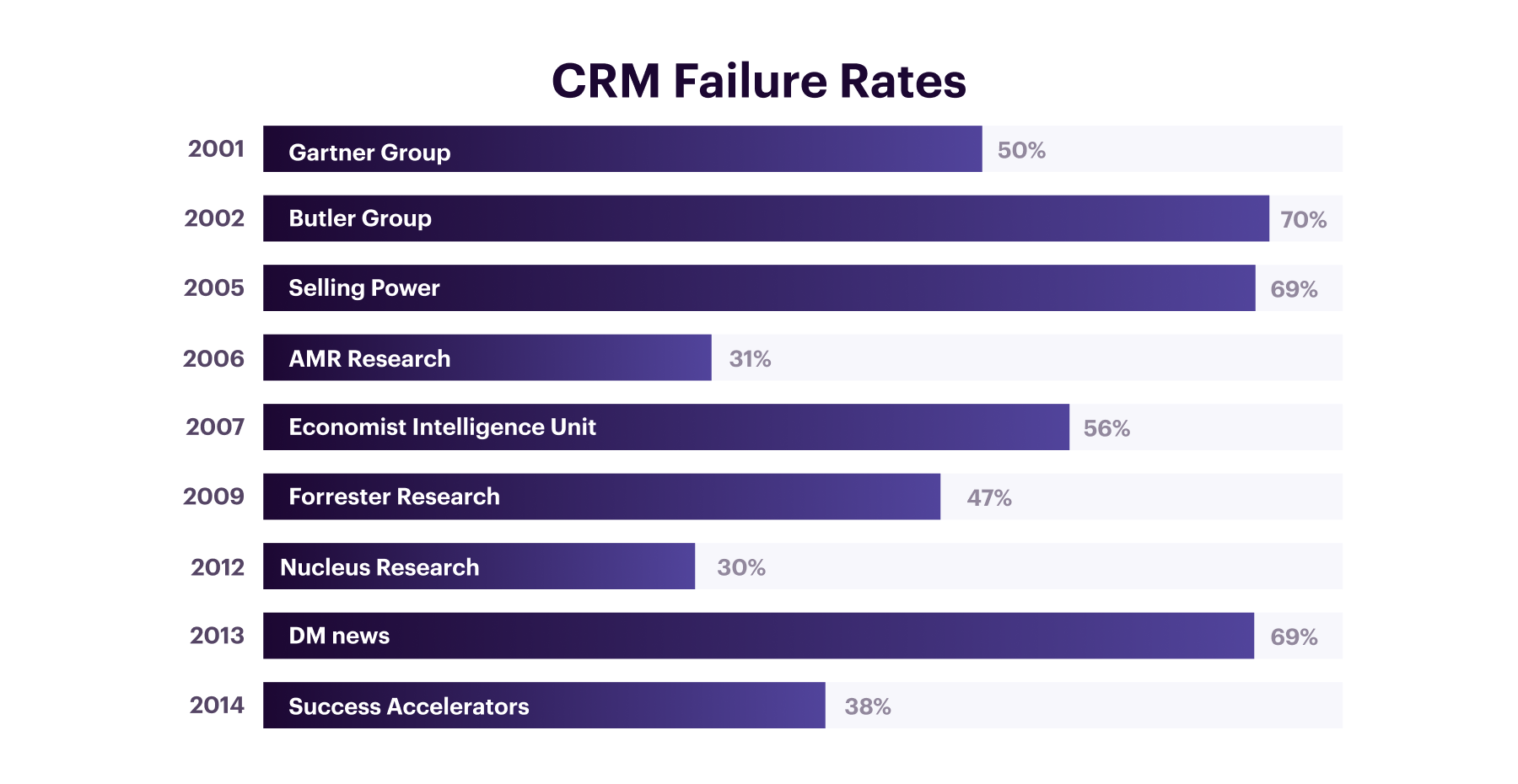

It wasn’t long before customers started feeling the side effects. By 2006, more than 50 percent of all CRM implementations were judged as failures by their customers.

A summary of CRM failure stats for the period 2001-2014. Source: Gartner

Businesses themselves weren’t faring much better. Throughout the 2000s, depending on who you like to believe, anything up to 70% of companies deemed their CRM implementation a failure.

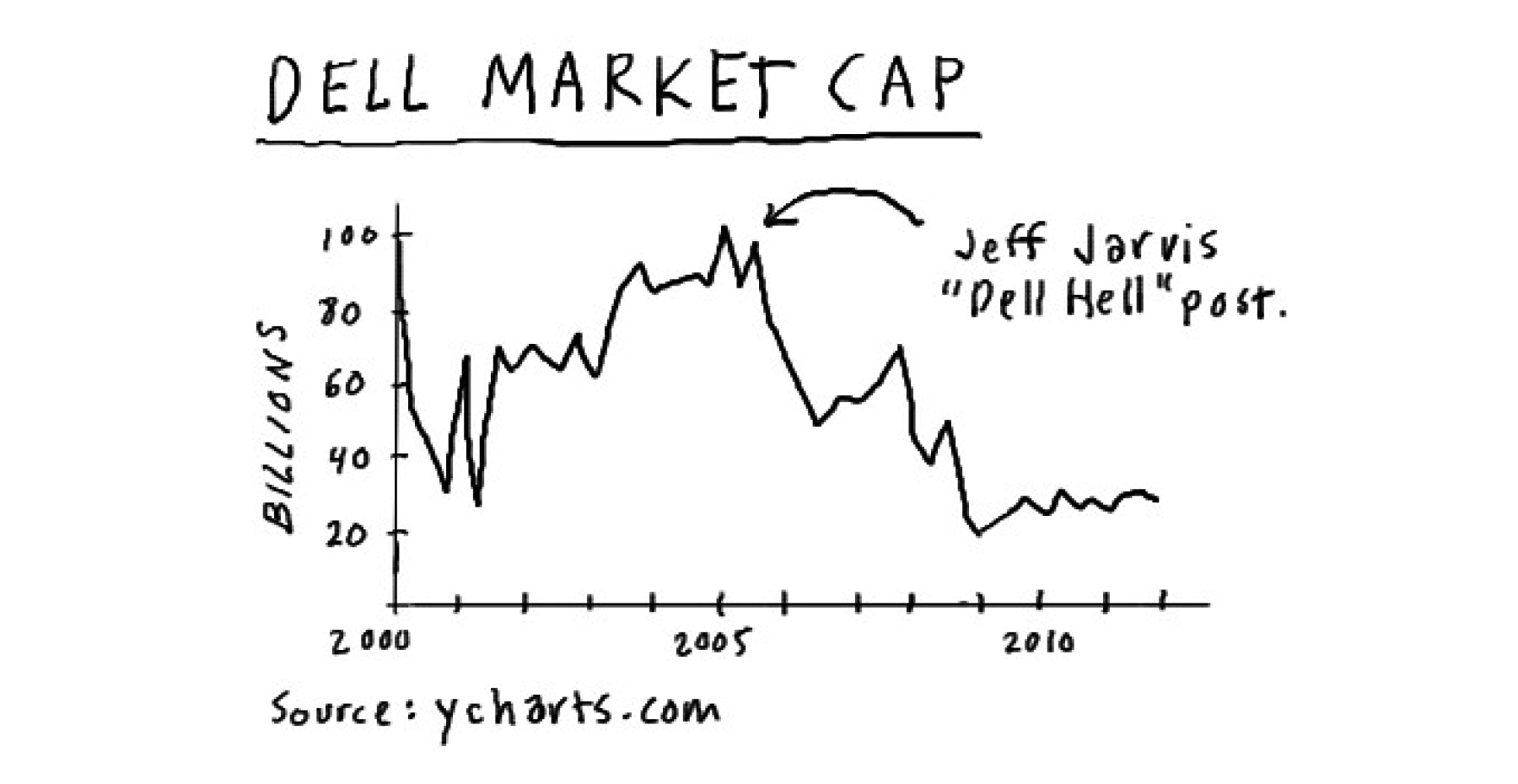

This mood of heightened customer expectations is best illustrated in the case of Jeff Jarvis and his Dell hell. On June 21, 2005, the Buzz Machine blogger and media consultant wrote a short, irate post. He’d just bought a laptop for which he’d paid a fortune.

Never mind that the thing didn’t work. What irked him most was what happened when he tried to get in touch. Bounced around from department to department, from rep to rep reading from pre-recorded scripts, nobody could find a record of his purchase.

These frustrating customer experiences were far from the future CRM had promised.

Two months later, with customers revolting, customer satisfaction scores falling, and market cap shrinking, he wrote an open letter to the CEO with some stark advice – engage with your customers, he said. Or pay the price.

How poor customer experiences cost Dell billions in market cap. Source: ycharts.com

It wasn’t long before commentators started the campaign for CRM 2.0, what Forrester referred to as “the social customer.”

For the past two decades, CRM had given businesses an inside-out view of the world. Known customers were mapped 1:1 to their purchases, and the resulting data managed according to a set of predefined categories defined by the business.

CRM 2.0 promised something different – an ‘outside-in’ perspective of the world.

Rather than jam customers into the businesses’ fixed notion of channels, scripts, and databases, it would cater to the unique preferences of each customer, by collecting data on the dozens of channels that a customer interacts with. Instead of working from one to one relationships, it would work one-to-many.

If the software itself was becoming more customer-focused, so too was the mechanism by which it was sold.

SaaS brought in a whole host of innovations to the industry. But one of the most underappreciated was that it changed the customer-vendor relationship irrevocably.

If a SaaS product doesn’t work out, the customer walks away. It’s on the vendor to ensure the success of the application.

By the 2010s, what was certain was that we had a world of heightened expectations. Customers expected more from businesses in their (increasingly online) experiences. And businesses expected more from vendors to help them facilitate these experiences.

But what was less certain was what software could fulfill those expectations. Would it be CRM 2.0, or something else entirely?

Marketing consolidation predictions throughout the 2010s. Source: Chief Martec

Once Salesforce had opened the floodgates of SaaS, its business model and efficiencies transformed the world of software. SaaS was the ship that launched a thousand products, attracting billions in venture funding and disrupting entire industries.

It wasn’t long before the likes of Adobe, Oracle, and Salesforce began to pay attention and started to acquire (and often sunset) hundreds of companies who had emerged from the SaaS boom. Many wondered whether this was a natural byproduct of the technology landscape reaching saturation point. It looked like the future belonged to one tool that would rule them all.

Except consolidation never came.

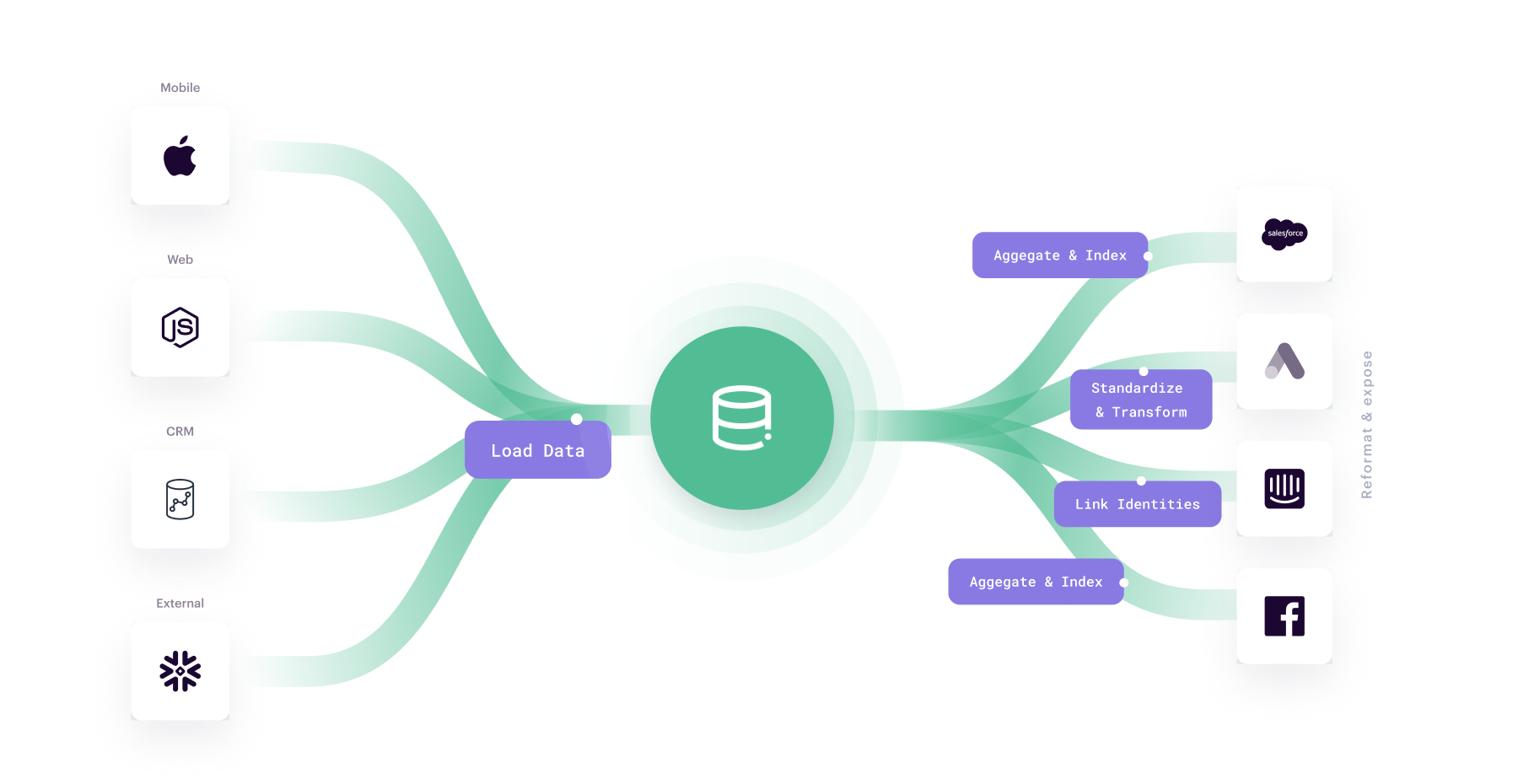

The evolution of the cloud, open-source software, and the API economy continued apace, and the technology landscape became more fragmented, not less. It was in this context, where businesses were using upwards of 100 different tools in their tech stack that David Raab coined the term “customer data platform.”

What Raab saw was the need for new software capable of pulling together disparate strands of data. “A company can easily have over 100 systems in place, pulling in customer data,” says Raab. “And they don’t necessarily talk to each other.”

Raab thought they really ought to.

Customer data platforms: a long-held desire to build a single view of the customer, finally realized.

As the founder of the vendor-neutral CDP Institute, his contention was that there was a gap in the market. All this data about customers, all sitting in different systems, yet few companies had a level of unified customer data necessary.

The opportunity to take all of this data, clean it, de-dupe it and merge it into a single table of customers with their dimensions and attributes, and unify it behind a single customer identifier was massive.

CDP was the utopia that CRM had promised us.

While CDP arrived with all the requisite froth of new marketing technology, it was, in fact, nothing new. The innovation, according to Raab, was that there was now prepackaged software that customers had already been building:

Companies have, for quite some time, been building custom databases to pull this data together. Now, CDP is the packaged software that enables that. David Raab

As it turned out, businesses were eager to offload undifferentiated heavy lifting to new CDP providers. Since Raab coined the term in 2013, the CDP category has grown from 19 providers to over 100, while funding has grown from $400 million to well over $2 billion.

So where does this leave CRM?

Far from sounding the death-knell of CRM, CDP has liberated it. By taking the lead on data collection – “the dirty work” – as Capterra’s Christopher Hogan likes to put it – CDPs are freeing CRMs up to do what they were designed to do – manage customer relationships.

Which today, Brinker says, is everything.

The way companies are differentiating themselves is less and less about the specific features of their products per se, and more about how delightful the experience of being a customer is. Scott Brinker

With CRM now free to focus on what it’s good at (sales and service), and CDP as the new system of record, it looks like we’re about to enter the third chapter of customer data software.

On October 19-22, we'll be hosting CDP Week, the premier industry conference for customer data leaders. We'd love if you could join us.

Our annual look at how attitudes, preferences, and experiences with personalization have evolved over the past year.