Each destination API uses a different request format, requiring custom code to translate the event to match this format. A basic example is destination X requires sending birthday as traits.dob in the payload whereas our API accepts it as traits.birthday. The transformation code in destination X would look something like this:

Many modern destination endpoints have adopted Segment’s request format making some transforms relatively simple. However, these transforms can be very complex depending on the structure of the destination’s API. For example, for some of the older and most sprawling destinations, we find ourselves shoving values into hand-crafted XML payloads.

Initially, when the destinations were divided into separate services, all of the code lived in one repo. A huge point of frustration was that a single broken test caused tests to fail across all destinations. When we wanted to deploy a change, we had to spend time fixing the broken test even if the changes had nothing to do with the initial change. In response to this problem, it was decided to break out the code for each destination into their own repos. All the destinations were already broken out into their own service, so the transition was natural.

The split to separate repos allowed us to isolate the destination test suites easily. This isolation allowed the development team to move quickly when maintaining destinations.

As time went on, we added over 50 new destinations, and that meant 50 new repos. To ease the burden of developing and maintaining these codebases, we created shared libraries to make common transforms and functionality, such as HTTP request handling, across our destinations easier and more uniform.

For example, if we want the name of a user from an event, event.name() can be called in any destination’s code. The shared library checks the event for the property key name and Name. If those don’t exist, it checks for a first name, checking the properties firstName, first_name, and FirstName. It does the same for the last name, checking the cases and combining the two to form the full name.

The shared libraries made building new destinations quick. The familiarity brought by a uniform set of shared functionality made maintenance less of a headache.

However, a new problem began to arise. Testing and deploying changes to these shared libraries impacted all of our destinations. It began to require considerable time and effort to maintain. Making changes to improve our libraries, knowing we’d have to test and deploy dozens of services, was a risky proposition. When pressed for time, engineers would only include the updated versions of these libraries on a single destination’s codebase.

Over time, the versions of these shared libraries began to diverge across the different destination codebases. The great benefit we once had of reduced customization between each destination codebase started to reverse. Eventually, all of them were using different versions of these shared libraries. We could’ve built tools to automate rolling out changes, but at this point, not only was developer productivity suffering but we began to encounter other issues with the microservice architecture.

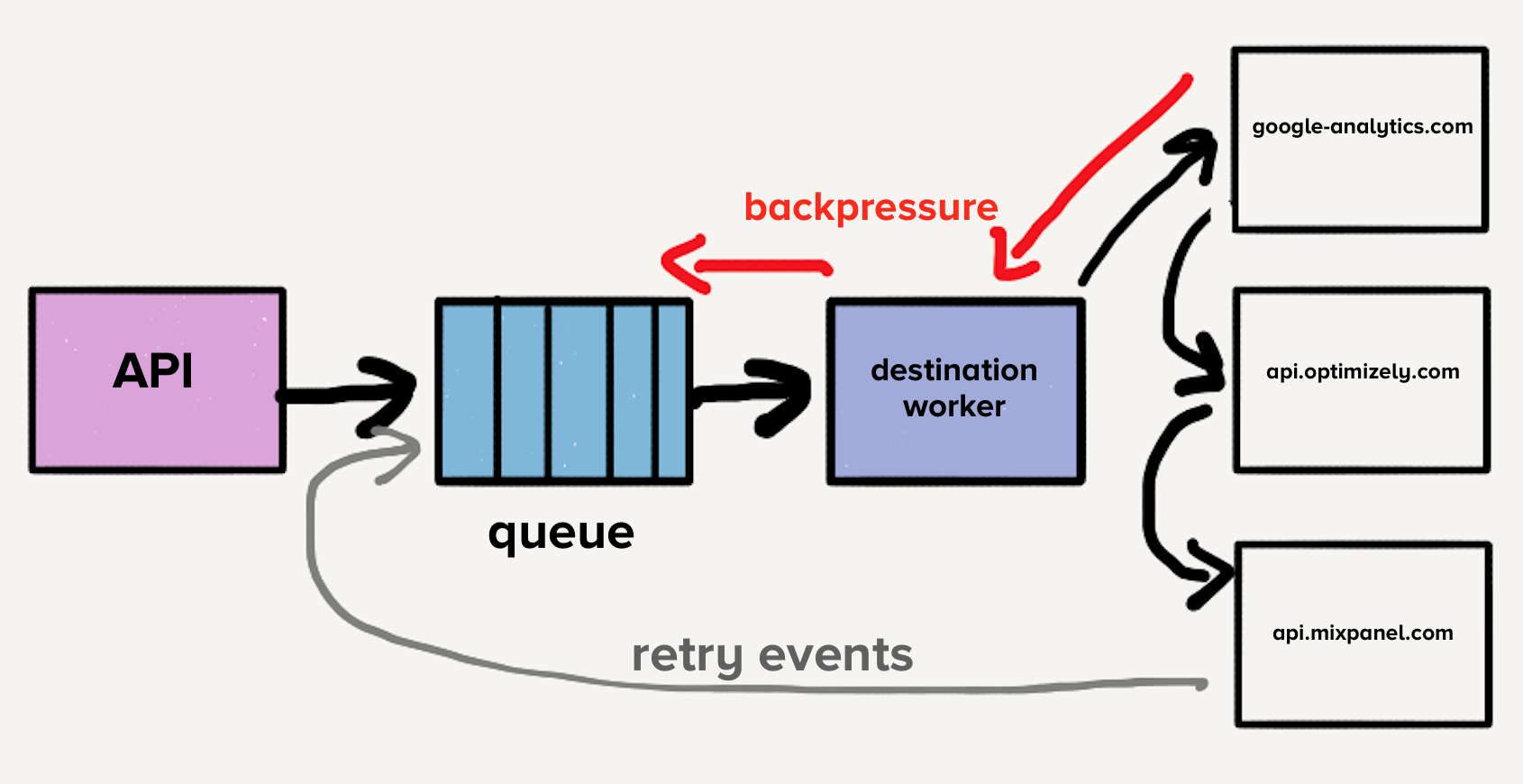

The additional problem is that each service had a distinct load pattern. Some services would handle a handful of events per day while others handled thousands of events per second. For destinations that handled a small number of events, an operator would have to manually scale the service up to meet demand whenever there was an unexpected spike in load.

While we did have auto-scaling implemented, each service had a distinct blend of required CPU and memory resources, which made tuning the auto-scaling configuration more art than science.

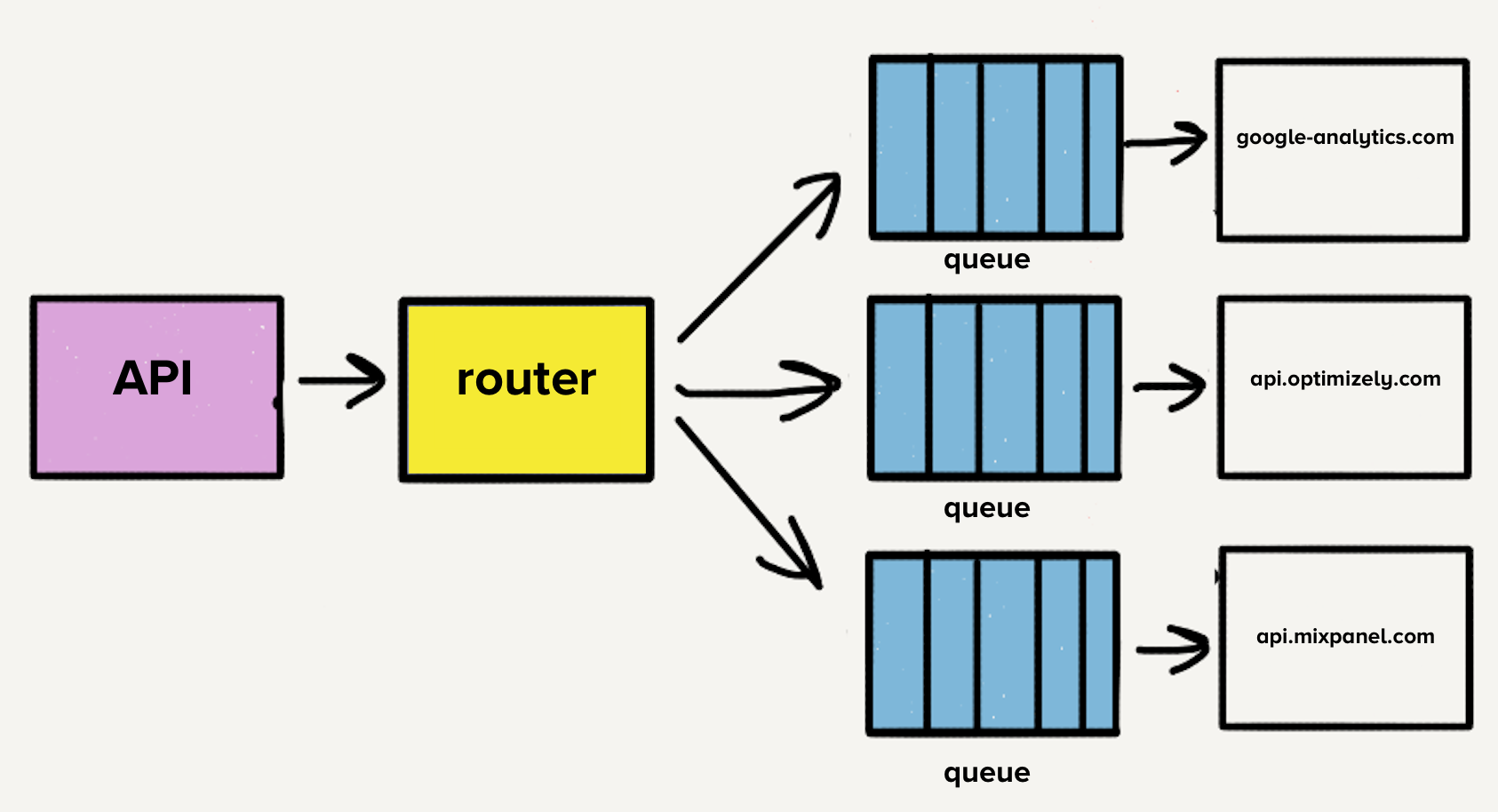

The number of destinations continued to grow rapidly, with the team adding three destinations per month on average, which meant more repos, more queues, and more services. With our microservice architecture, our operational overhead increased linearly with each added destination. Therefore, we decided to take a step back and rethink the entire pipeline.

The first item on the list was to consolidate the now over 140 services into a single service. The overhead from managing all of these services was a huge tax on our team. We were literally losing sleep over it since it was common for the on-call engineer to get paged to deal with load spikes.

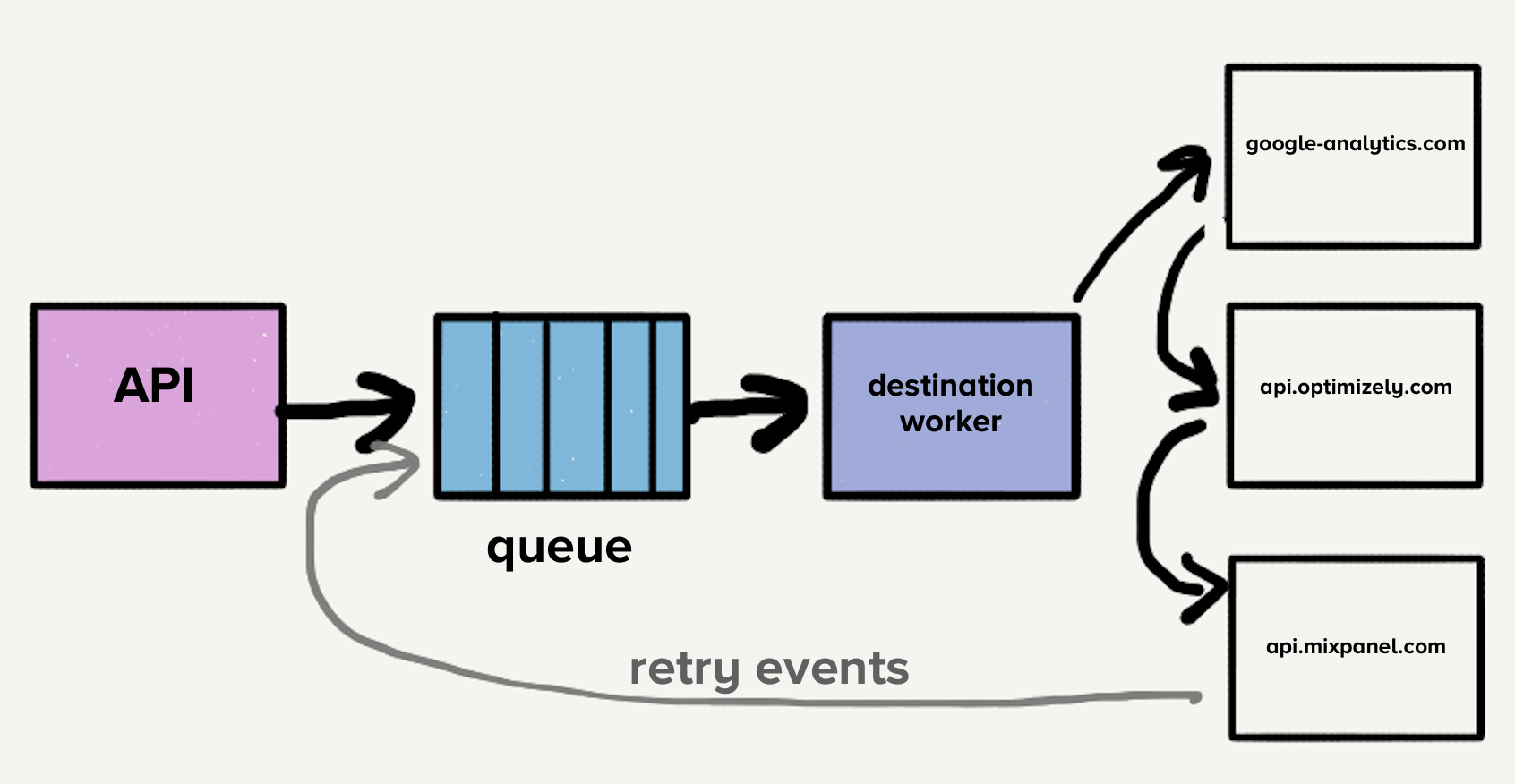

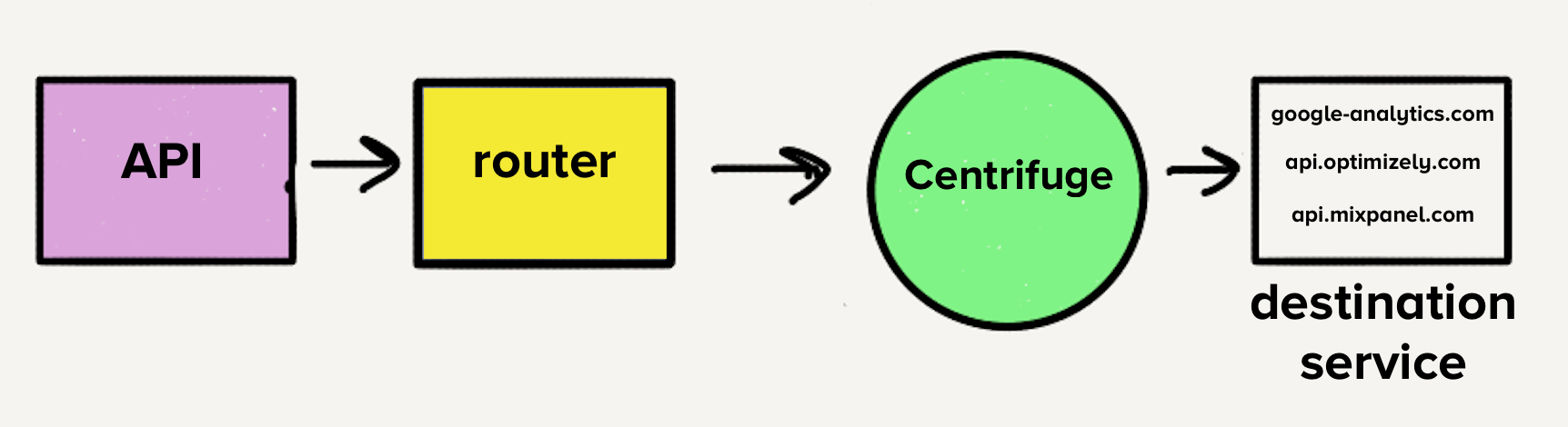

However, the architecture at the time would have made moving to a single service challenging. With a separate queue per destination, each worker would have to check every queue for work, which would have added a layer of complexity to the destination service with which we weren’t comfortable. This was the main inspiration for Centrifuge. Centrifuge would replace all our individual queues and be responsible for sending events to the single monolithic service. (Note that Centrifuge became the back-end infrastructure for Connections.)